As the Army brings back its classic, “Be All You Can Be” advertising campaign, we revisit the strange tale of brand reinvention that originally led to its demise.

Since this column is called Reinvention Notes, I thought that this month we would look at Brand Reinvention. Recently I read an article about how the US Army is bringing back its classic, “Be All You Can Be” brand advertising campaign, as they struggle to meet their recruiting numbers. I thought, who better to explore this than someone who helped kill this strategy over 23 years ago?

“Be All You Can Be”

Before we get started, I want to establish that I liked the old “Be All You Can Be” advertising. Growing up as an ‘80s teen, the Army’s ad campaign was deeply ingrained in my subconscious – it even drove the plot of the classic ‘80s movie “Stripes.” At the time I don’t recall feeling that the campaign compelled me to visit a recruiting center, but I was in Canada back then and I wasn’t entirely sure that we had an army.

For those of you who haven’t seen it, the advertising was full of people jumping out of planes, crawling under barbed wire, and doing stuff that “teen me” thought was really cool. And that was the target: young people deciding what to do with their lives. The big chunk of young America for whom college may have been out of reach, those who hadn’t yet found their thing. The Army was positioned as an exciting alternative that challenged you to push past your limits. It would help you figure out what you want to do with the rest of your life, and maybe give you a free ride to college (of course nothing is really free).

And then something happened. The Cold War ended. The battle that the US Army had spent half a century preparing for was abruptly canceled. People went on with their lives. But as it turns out, even without a big enemy, an Army still needs a lot of soldiers.

The US still had troop commitments to Germany, Korea, and elsewhere, and instead of fighting one big war, the US preparedness strategy was now about being ready to fight two mid-sized wars simultaneously. At the turn of the millennium, this amounted to the need for about 100,000 new recruits every year, just to stay even with those who left the service or retired.

So, what’s this got to do with branding? As it turns out, a lot. Just as the Army described itself as “the toughest job you’ll ever love,” it was also one of the toughest brands to have to sell. Think about what is being sold…you will have to work very hard, in often unpleasant conditions, you will be bossed around and may be yelled at, the hairstyle you like – gone, you will be paid very little, and there is the ever-present risk of serious injury or death. Now just sign here.

Until the end of the Cold War, the US Army’s recruiting mission relied on the brand intangibles created by having an imposing enemy – duty, honor, and patriotism. With America’s enemies apparently vanquished, these intangibles were pushed to the background, and the Army missed its recruiting mission every year from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the turn of the century. Sure, there were still young people primarily motivated by duty, honor, and patriotism, but many of these were sopped up by the niche but very well-targeted brand, the Marines. There was no surplus to feed the biggest recruiting need, the US Army.

The Assignment

The engagement had 3 primary deliverables (the third deliverable is a story for another day):

- Develop the Army’s brand strategy and positioning

- Identify the new Army advertising agency

- Build a modern marketing organization and capability for US Army recruiting

Despite the scope and scale of this work, the core team was remarkably small – me as the Senior Engagement Manager, along with an insights consultant, and a consultant with an ad agency background.

Brand Discovery

Freshly laminated security passes in hand, we met our client “handler” at the Pentagon – a Lieutenant with a southern drawl, whose name I genuinely remember as “Bubba.” He showed us around the massive Pentagon complex, ending the tour in a center courtyard with a small stone building. We were told that during the Cold War, the Soviets targeted this building with ICMBs, believing it to be the entrance to the high command’s bunker. In actuality, it was a hot dog stand where we had lunch. Maybe this was just a southern tall tale Bubba was telling us, but it’s never good to question your clients too much on your first day.

We were given an office near our clients that was filled with abandoned office furniture from what we imagined was the Truman administration. Inside the drawer of one of the desks was a stack of blank commendation forms, which I didn’t want responsibility for and quickly handed off to Bubba. As I looked around the place I came to the realization that while the US military may command a budget that now approaches $2 trillion dollars, they weren’t spending it on their creature comforts.

Our discovery work involved interviewing a great number of stakeholders, both military and civilian, who were lovely to us. On one general’s wall was a picture of President George H. W. Bush skydiving with the US Army’s Golden Knights. I was looking at the photo as our meeting was wrapping up and the general said something like, “Looks like fun, doesn’t it?” Without thinking too much, I said, “Sure.” He immediately made a phone call and 3 days later we were at Fort Bragg jumping out of an airplane – an amazing experience that I will never do again. To this day, I don’t know if this was an incredible act of hospitality by the general, or a failed attempt to get rid of the consultants.

The discovery tour continued on to the US Army Recruiting Command, Fort Hood, and at Fort Knox we got to operate the tank simulators that Tank Drivers train on (and yes, they are called Tank Drivers).

Consumer Research

When it came time to conduct the consumer segmentation research that would drive our brand strategy, we were asked by the Army’s civilian leaders to collaborate with the RAND Corporation, which is a storied “think tank” closely affiliated with the Department of Defense. While we didn’t really need help with segmentation research, I was very intrigued about learning what goes on at a “think tank,” and it helped that RAND’s HQ was across the street from the wonderful, Shutters on the Beach in Santa Monica.

One of RAND’s recommendations which we were encouraged to adopt, was that the research sample should be well over 10,000 respondents. Up to then, I had never worked with such a large sample in my life, for two good reasons: 1) corporate clients would never fund such extravagance, and 2) statistically, it was completely unnecessary to get to 6-8 actionable segments. I just assumed it was part of the “$600 toilet seat” type of overkill that the DoD was known for and moved forward.

Positioning Insight

10,000 surveys in hand, we set about creating the segmentation. Right off the bat, some segments fell off as potential targets, including the ones who would never consider the Army, as well as the ones who would always prefer the Marines or other branches.

Two of the remaining segments shared characteristics that made them interesting as targets. They weren’t looking for the Army to shape or transform them, they just needed a leg up. They wanted to build a better future for themselves but didn’t necessarily have all the options that you or I might have had at that age. For these young men and women, the Army had a compelling story that wasn’t being told.

We learned that the Army wasn’t “one” type of job but actually over 220. A great many of these Military Occupational Specialties (MOSs, as they called them), were “real-world” jobs with analogies outside of the Army – surveyors, mechanics, programmers, and countless other vocations. Since the Army can’t win the war for this talent against employers paying market wages, it trains its people in these professions. These are skills that could seamlessly transition to a civilian career after a few years in the service. This was exactly the leg up these segments were looking for but didn’t realize the Army offered.

We crafted the positioning to speak to these young people with their “eyes on the horizon,” and set out to educate them about this unsung Army value proposition. To validate the strategy, we took existing Army television advertising and re-edited it with a voiceover of our story and put it into testing, along with current and historic advertising. The messaging tested 2X stronger with our target than what the Army had been airing, including “Be All You Can Be.”

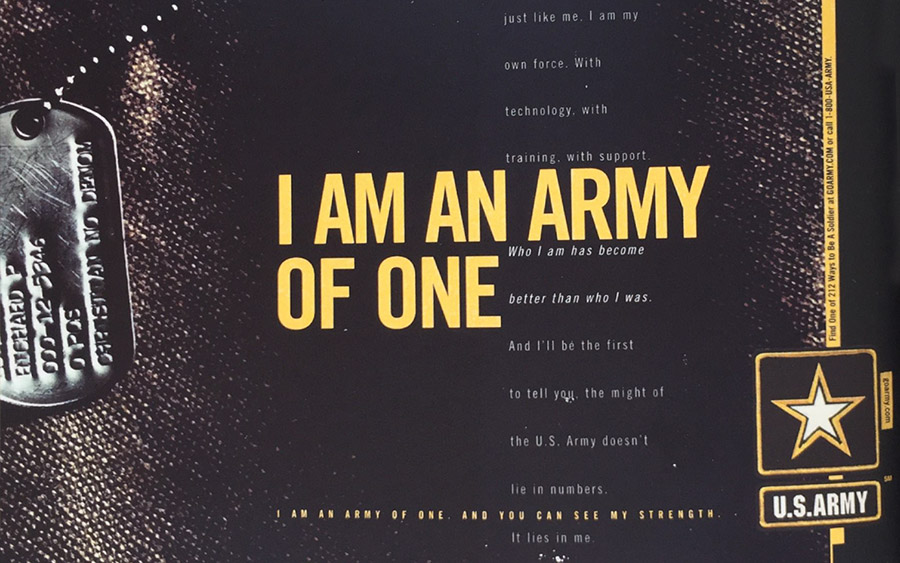

An Army of One

If an animatic tested that well, imagine what results you could get with a real production budget. Bringing to life the new positioning involved selecting a new advertising agency. McCann came to the pitch with presentations bound in cool stainless-steel boxes, so there was little doubt about who win this assignment.

There is always a little loss of fidelity in translating brand strategy to creative strategy. Sometimes this process elevates everything, sometimes not. You are probably familiar with the Army of One advertising that resulted from this work — it even became the title of a Sopranos episode.

I thought the campaign was good but misinterpreted the target segment somewhat. Their focus on their future didn’t make them lone-wolf – these were team players wanting everyone to succeed. But the strategy and advertising worked as intended. Within a matter of months, a decades-long decline in recruiting was starting to turn the corner.

The Context Changes

The consulting team involved in the Army branding effort went on to successful careers and full lives. Some of our clients didn’t get that opportunity. On September 11, 2001, a plane crashed into the west side of the Pentagon, which housed the Army Office of Personnel, killing our senior Army client.

Lieutenant General Tim Maude was the highest-ranking military officer killed in the 9/11 attacks, and the most senior American officer killed in action since World War II. He was the U.S. Army’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel, who had recently relocated his office directly into the path of American Airlines Flight 77. The consulting team’s former office was just down the hall.

I can’t say I knew General Maude very well, but what I observed was a soft-spoken and kind man who was deeply respected by the people he led. He was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery, befitting of a hero who gave his life in service to his country.

The core of the team that served the Army had gone on to rebrand work for a Caribbean financial service conglomerate. We saw the attacks play out on a small TV outside a board room in Barbados as our final review was taking place. After some time, the CEO suggested that we continue the meeting.

9/11 changed the recruiting mission of the United States. The enlistment ranks swelled with those drawn by a sense of urgency to protect their country, and the career “MOAs” shifted disproportionally to the battlefield roles.

Brand Learning

Maybe it’s a fool’s errand to attempt to find generalizable learning from this most unusual of brand stories, but I’m just the fool to try. One obvious takeaway is that context changes – sometimes dramatically, and brands must adapt. It’s hard for me to think of other category analogies that compare to just how much and how quickly the US Army brand’s context can shift, but it’s a matter of degree.

Most business categories today are confronting some form of disruption that is requiring companies to embrace reinvention. But brands are in many ways more difficult to change than business models. They can pivot, they can stretch, but how far and how fast depends on what lies at the brand’s core.

Vivaldi’s Brand Identity System helps us understand what lies at the core of a brand that is enduring, versus the elements of the brand that are more temporal and subject to change. Duty, honor, and patriotism lie at the core of the Army’s brand identity. While what is going on in the world may make these more or less top of mind, they are never far from the surface.

These values and the character of the men and women who serve the Army are enduring, even while the context shifts from focusing on careers to prosecuting wars. Communicating this proposition effectively to meet the Army’s recruiting mission in times of both war and peace is one of the toughest branding assignments out there.

***

To all the men and women serving in the Army – thank you for your service.