Making the Metaverse Work for the Rest of Us: Part I

In this series of three articles, I’ll discuss the metaverse and Web3 — or Web3+ — given that the prolific Jack Dorsey announced Web5 and Snoop Dogg announced that he is already working on Web6. I’ll also discuss the significant implications that these evolving and still immature technologies will have on companies and brands, and what impact they will have on how consumers will live in the future.[1]

My thesis is a simple one. If you want to assess whether these new technologies are important to you, where there are opportunities for your company to create a competitive advantage, connect with consumers, build a sustainable new business or achieve new growth, you need to analyze and understand how these technologies will change how consumers live, play and work in the future. Fortunately, we can already see glimpses of these changes on consumers today.

This first article aims to establish whether the metaverse or Web 3+ is a thing, and whether we really should bother at all. I’ll offer a brief recursion in the recent past. I think this is helpful in the sense of what Albert Einstein once said: “If you want to know the future, look at the past.”

The second article will introduce a framework and model that we at Vivaldi find helpful. It is a way to understand these technologies, how they help achieve business goals, and how they affect consumer behavior and society. This framework is the interaction field model. A model or framework is a way of choosing what information is important and which information is not. The model I propose helps to sort out what really matters, what you should attend to and look out for, and what is merely noise, hubris, hucksterism, hype, speculation, gambling, unsavory works or even criminality, so often reported by the press.

The third article will describe actual applications and case studies of how the metaverse or the Web3+ technologies impact companies and industries and how value is created for consumers and society. That is, how it impacts the rest of us, beyond those that make it a business such as the speculators, futurists, boosters, thrill seekers, experts, fortune tellers and others. But before we get there, allow me to first briefly describe how we got here. This will set the stage and answer a simple question: Is the metaverse or Web3+ a thing or not?

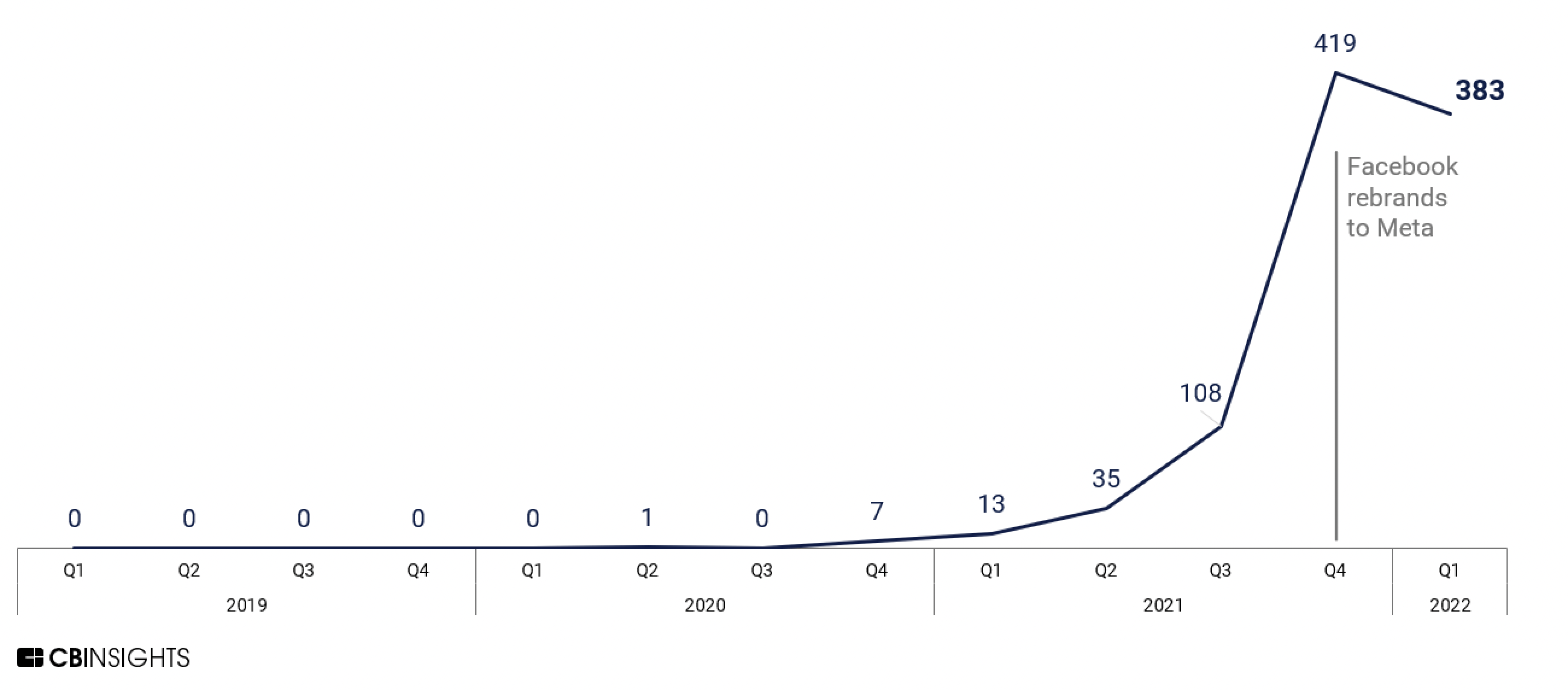

The answer is: yes. This chart from CBInsights, which shows the frequency with which the word “metaverse” was mentioned on earning calls, shows when it became at least a very exciting movement; a lofty vision with enormous energy and enthusiasm —even if it is still not quite real.

Earnings Call Mentions of “metaverse”

October 21, 2021 is when this hypothetical, notional, alternative lofty vision and digital domain, called the metaverse became a thing. That day is the Metaverse’s equivalent of the Mayflower touching shore near Plymouth Rock. That’s when then-Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg rebranded the firm “Meta,” to signify the seriousness with which the company was taking “the next generation of the Internet.” At the stroke of a press release, Zuckerberg pulled the metaverse from the further reaches of futurist fantasy into the here and now. In the coming years, he predicted, “People will transition from seeing us primarily as a social media company to seeing us as a metaverse company.”[2] To which, those of us more deeply engaged with all things IRL (tech-speak for “In the Real World”) could be forgiven for scratching our heads.

October 21, 2021 is when this hypothetical, notional, alternative lofty vision and digital domain, called the metaverse became a thing. That day is the Metaverse’s equivalent of the Mayflower touching shore near Plymouth Rock. That’s when then-Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg rebranded the firm “Meta,” to signify the seriousness with which the company was taking “the next generation of the Internet.” At the stroke of a press release, Zuckerberg pulled the metaverse from the further reaches of futurist fantasy into the here and now. In the coming years, he predicted, “People will transition from seeing us primarily as a social media company to seeing us as a metaverse company.”[2] To which, those of us more deeply engaged with all things IRL (tech-speak for “In the Real World”) could be forgiven for scratching our heads.

No sooner had brands and businesses cottoned on to the idea that the metaverse might just be the next big thing, when Microsoft jumped into the fray, in a big way. Analysts applauded its bold $70 billion bet on gaming juggernaut Activision Blizzard as a major metaverse play, in light of the golden opportunity it presented to marry software — games like World of Warcraft and Call of Duty – to hardware. Microsoft’s HoloLens VR/AR technology up until then had been mainly a B-to-B tool. Driving the point home, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella used the term “metaverse” five times on the analyst’s call, extolling it as primarily a 3D gaming experience.

The metaverse is…about creating games…To me, being great at game building gives us the permission to build this next platform, which is essentially the next internet: the embodied presence. Today, I play a game, but I’m not in the game. Now, we can start dreaming [that] through these metaverses: I can literally be in the game, just like I can be in a conference room with you in a meeting. That metaphor and the technology . . . will manifest itself in different contexts.”[3]

Zuckerberg, for his part, dealt out a dueling definition:

You can think of the metaverse as an embodied internet, where instead of just viewing content — you are in it. You feel present with other people as if you were in other places, having different experiences that you couldn’t necessarily do on a 2D app or webpage, like dancing…or different types of fitness.[4]

In a “Meta Founder’s Letter,” he delved deeper into the details:

The defining quality of the metaverse will be a feeling of presence. It will feel like you are right there with another person or in another place. Feeling truly present with another person is the ultimate dream of social technology…In this future, you will be able to teleport instantly as a hologram to be at the office without a commute, be at a concert with friends, or be in your parents’ living room to catch up. This will open up more opportunity no matter where you live. You’ll be able to spend more time on what matters to you, cut down time in traffic, and reduce your carbon footprint.[5]

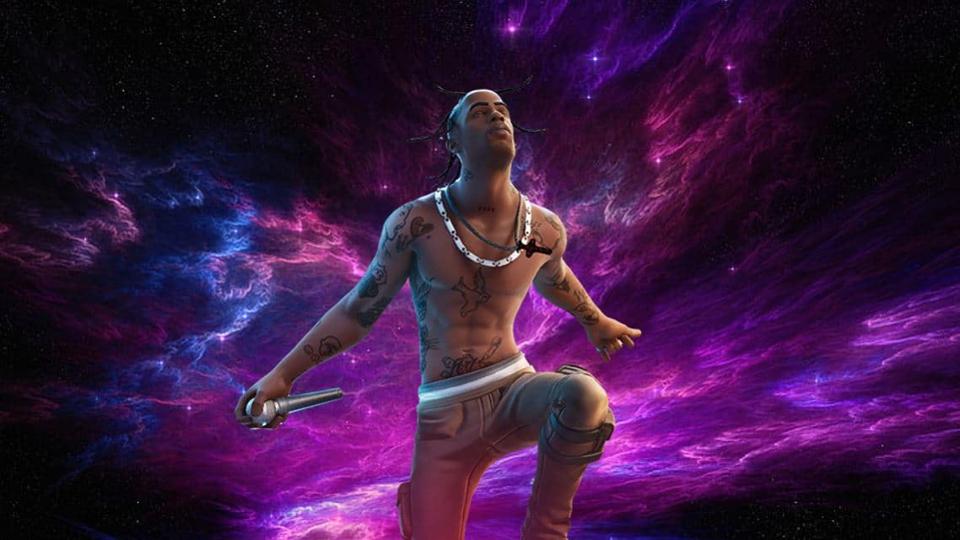

Travis Scott on Fortnite

As if on cue, these blue-sky pipe dreams were reified by a succession of major Metaverse moments. An anonymous bidder laid out $450,000 in cryptocurrency for a plot of virtual land adjacent to rapper Snoop Dogg’s virtual estate, both “located” in an upscale district of a self-styled metaverse called Sandbox. A Travis Scott concert held in the gaming metaverse of Fortnite pulled in 27.7 million attendees, vastly outdrawing any conceivable real-world counterpart. JPM Morgan Chase, most unabashedly bullish of the big banks, approvingly noted: “In Decentraland, a user-owned Ethereum-based virtual world, 21,000 real estate transactions totaled $110 million in 12 months. Virtual real estate is a growing market. The average price of a parcel of land doubled in a six-month window in 2021. It jumped from $6,000 in June to $12,000 by December across the four main Web 3.0 metaverses.”[6] The concept gained real credibility on Wall Street with the $40 billion blockbuster IPO of Roblox, a firm famed in Fortune for creating “an immersive virtual world of gamers with a following that has spread far beyond young STEM nerds.”[7] What made Roblox stock so hot was that a holy host of consumer brands, including Disney, Nike, the NFL, and Chipotle, had lately staked out first-mover claims on its virtual frontier. The buzz only intensified after the digital pop-up store Gucci Garden sold a limited-edition virtual version of its exclusive Queen Bee Dionysus handbag for a higher price than in IRL: $4000 over $3600.[8] Also on Roblox NIKELAND offered a virtual version of Nike HQ, with the added attraction of visitors using accelerometers on their phones to “translate activity in the physical world into longer jumps or faster speeds” in the metaverse.[9]

As the buzz and hype amplified to deafening levels, a chorus of skeptics pushed back. Leading the contrarian pack, Elon Musk dismissed the concept as “all hype and no substance,” if for no other reason than the current crop of AR/VR headsets were clunky, costly, and dorky. “You can put a TV on your nose but I’m not sure that puts you `in the metaverse’” Musk scoffed. “I don’t see somebody wearing a frigging screen on their face all day and refusing to leave…I don’t believe we’re on the verge of slipping into the metaverse. It has the ring of a buzzword.”[10]

Pushing back on the pushback, not so surprisingly, was the sector best positioned to benefit from the vision becoming reality: consumer electronics companies. Forever on a quest for the next big thing to replace maturing legacy technologies in the hearts and minds of consumers, in early 2022 over 2,000 tech companies descended on the IRL fantasy land of Las Vegas for the first in-person CES (Consumer Electronics Show) in two long pandemic years.

Samsung’s NFT TV

Observing from the sidelines, Axios tech journalist Ina Fried dryly noted: “Many CES observers suggested a drinking game in which keynote watchers took a shot every time the metaverse was mentioned. But that would have been a recipe for alcohol poisoning.”[11] Boosters prowling the booths, however, could point to, touch, feel and in some use-cases wear tangible products tailored to meet the moment. From Panasonic subsidiary Shiftall: a body tracking suit designed to extend VR experiences beyond the head and torso. From startup Pebble Feel: a body-worn accessory that lets its wearer “feel” virtual heat and cold; from yet another startup: a “haptic jacket” that permit wearers to “feel” virtual sensations. From Sony: PlayStation VR2, complete with “new sensory features” like eye-tracking, enabling users to swivel their vision from right to left. From Microsoft: a partnership with Qualcomm to develop lightweight AR glasses. From Hyundai: grand plans to build “digital twin” factories, yet another key facet of the evolving metaverse, touted as potentially re-inventing manufacturing. From Samsung: a TV to display your growing collection of Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) for the bros on the block.

The Dawn of Web3

Samsung’s NFT TV was one of the only tangible hardware nods there to a potentially competing paradigm, Web3, whose proponents argue with a quasi-religious fervor that the “3D immersive experience” is not the main act but a side-show compared to the radically transformative economics of shared value among and between digital denizens. Web3+ seeks to unshackle the digital economy from sovereign authorities like central banks and private enterprises that thrive within the current global financial ecosystem. In Web3+ future world, late-stage capitalism withers away, to be replaced by decentralized, self-governing, anonymized forms of finance, of which the current crop of cryptocurrencies are merely the first crude iterations.

The term Web3 was first coined in a 2014 online treatise by Ethereum blockchain cryptocurrency co-founder Gavin Wood, who contended that this new and improved digital domain’s defining attribute, “pervasive privacy,” was only attainable through the adoption of “identity-based” pseudonyms. A core tenet of Web3 is that key to tapping into the magic of financial disintermediation and decentralization is unpierceable anonymity. [12] As a purely practical matter, however, IRL protocols aiming to protect privacy by promoting anonymity have succeeded thus far mainly to put widely speculative and in some cases, quasi-criminal forms of finance at the heart of a putatively noble experiment. An unrelenting focus on safeguarding anonymity at all costs has, to its critics, served mainly to amplify abuses, including but not limited to hacking, groping, snooping, and stealing, which have turned Web2 into a moral and social cesspool over the past two decades.

In the eyes of those critics, the most damning dark side of Web3 is that its most conspicuous beneficiaries are younger, scruffier versions of the original Silicon Valley male mafia. In Vice, early Web3 adopter Tim O’Reilly conveyed his dismay that “blockchain has turned out to be the most rapid recentralization of a decentralized technology I’ve seen in my lifetime.”

Accounting for its vested interest in advising large enterprises on how to dispense the staggering tech investments needed to make the big leap into the digital unknown, Accenture insists the two trends – Metaverse and web3 – are converging. “Either Metaverse or Web3 alone would be enough to draw hype and attention,” Accenture maintains. “But the fact that they are unfurling simultaneously is what demands enterprise leaders take notice.”[13] The firm draws a useful distinction between the two trends:

“These evolutions are taking place on two fronts: metaverse [is] the re-platforming of digital experiences…Web3 is reinventing how data moves through that system.”

Prophets of the Metaverse

Venture capitalist Matthew Ball, the most fluent prophet-protagonist of what he calls a “quasi-successor state to the mobile internet,” defines its realization as predicated on a specific set of prerequisites. His top three: scaling, to exponentially increase the number of potential participants to “infinite”; persistence, enabled by pervasive 5G networks to “improve immersion and create new experiences”; and interoperability, to enable economic value, experiences, and identities to be portable among multiple metaverses.

Counterpoint to the prophesizing and proselytizing came again from Axios’s Ina Fried, who did a quick reality check on the metamorphosis’ minimum timeline from the sidelines of the 2022 Mobile World Congress in Barcelona:

The full vision of a shared, 3D digital dimension…is probably still a decade away — but it won’t arrive out of nowhere in one piece. Instead, it will show up in bits and chunks, clunky and disjointed, before coalescing into something both functional and useful. Unless, of course, all this turns out to be another false start for a VR industry that has been promising us one metaverse or another for three decades now.[14]

By Way of Background

In his 1992 fantasy novel Snow Crash, science fiction author Neal Stephenson (three decades on, fittingly, a futurist at pioneering virtual reality firm Magic Leap) concocted a compelling mash-up of utopia and dystopia, ushering the term “metaverse” into the vocabulary of tech-geekery and elevating it to canonical status among self-styled Silicon Valley visionaries. In the book’s fictional IRL, Los Angeles is no longer part of the United States because the federal government has ceded much of its power and territory to private enterprises in the wake of a global economic and social collapse. Across what is left of the nation, mercenary armies compete for defense contracts while elites hunker down in guarded gated housing developments known as burbclaves.

The 1992 fantasy novel that used the term “metaverse”

The City of Angels, where the story is set, is threatened by waves of hungry Eurasian refugees approaching a Gold Coast densely settled by billionaires who live the high life on obscenely huge yachts.[15] In this bifurcated collision of “real” and “virtual” worlds, the ironically named Hiro Protagonist is a loser-slacker-computer hacker who lives in a shabby shipping container and delivers pizza IRL. Upon entering the metaverse, however, he transforms into a hero on a mission: tracking down the source of a nasty computer virus inflicting brain damage on users IRL. Thirty years later, Stephenson modestly admitted to “just making shit up.”[16] Still, Snowcrash’s metaverse uncannily prefigures today’s Roblox and Decentraland, among other proto-metaverses. It’s an urban fantasy amusement park, where virtual visitors spend vast amounts of cryptocurrency on speculative real estate and trivial pursuits and patronize boutiques along a Main Street thousands of miles long. Avid participants develop unhealthy addictions to the virtual world, and escape to the metaverse to disconnect from dystopian reality.

To today’s thinkers pondering the pros and cons of this virtual vision ever becoming reality, it’s hard to deny its potential to turn in on itself, as a digital extension of all-powerful of surveillance states, ruled by big government, big business, or worst-case scenario, both. Whether it’s Big Brother or Big Boss, The Wall Street Journal cites Electronic Frontier Foundation general counsel Kurt Opsahl on the disturbing prospect of your supervisor being equipped with the ability to track and record with uncanny accuracy the attitudinal implications of your subtlest eyeroll or shrug being monitored in a virtual meeting. “If coupled with data about body temperature or heart rate from a smart watch, the information could be used to try to infer a worker’s emotional state.” [17]

Small solace on that front may be gained from some sobering research conducted by the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCHD), a nonprofit that analyzes and seeks to disrupt online hate and misinformation. After staffers spent 12 hours recording activity on VRChat, the proprietary virtual world platform accessible via Meta’s Oculus headset, “the group logged an average of one infringement every seven minutes, including instances of sexual content, racism, abuse, hate, homophobia and misogyny, often with minors present.”[18] Nina Jane Patel, vice president of metaverse research for Kabuni, an immersive technology company based in the U.K., was, by her own account which promptly went viral, happily immersed in Meta’s Horizon Venues when her female avatar was “virtually groped and harassed” by a group of three avatars with male voices. “Before I knew it,” Patel maintained, “they were groping my avatar…[and] touching [its] upper and middle portion of my avatar…while a fourth male avatar was taking selfie photos of what was happening.”

In response to her sordid user experience, Meta rapidly rolled out a “default personal boundary” requiring avatars to stay nearly 4 feet apart from each other. That said and done, how is that enforceable in perpetuity? Given Meta’s checkered track record pitting profit up against the costs associated with safeguarding users’ privacy and dignity on Facebook, Meta’s baby step, however well intentioned, was anything but reassuring.

Fast Forward

If the metaverse and Web3+ is a world we dream of, and is indeed still years off, the lure of it has been unstoppable despite some enormous headwinds and dire turmoil in recent weeks and months.

All major crypto currencies have declined over the months with Bitcoin losing over 70%, and Ethereum losing as much in just four months, while a number of firms, including Celsius, the biggest lending platform, stopped trading due to insolvency risk. Terra UST and stablecoin LUNA wiped out over $40 billion of investors’ wealth in just 24 hours.

Some enthusiasts will quickly point out that crypto has survived major crashes before. It dropped 99.9% in 2011, and it dropped from $1,100 to $200 in 2013, in just a month. And then again, it dropped from $20,000 to $4,000 in 2017. Every time it dropped, it kept coming back stronger. Alex Dovbnya asked “Black Swan” author Nassim Nicholas Taleb whether the crash is just another crypto winter or a full-blown ice age. [19]

Others will say that we need to look beyond crypto, and even beyond the core technology of Web3+, namely the blockchain. This is a fair point. There are two ways to think about this one. First is to confide in experts, those that study the metaverse and the future more profoundly than everyone else. From this perspective, the metaverse will be a thing. McKinsey estimates it to be a $5 trillion economy. Goldman Sachs believes the metaverse will be a $8 trillion opportunity and Citi even estimates it to be worth $13 billion by 2030. These are staggering numbers. In order to get a sense of how big these numbers are, remember that today’s fashion industry is a $1.5 trillion global industry, and retail is about $6.6 trillion in the US. Even while these industries are so much smaller than the metaverse, they’re pervasive and important in our lives, which will make the metaverse a real thing for consumers and society.[20]

The second perspective is a personal one. I came to this country in 1995 and was told there was a company that had started to sell books online and we’d all read books and publish online. I smiled in disbelief wondering whether I missed something in translation. Some said that we’d buy cars and houses online, and even work there. They talked about an internet where you could find everything thanks to a search engine such as Google. A sort of goldrush took place, but by 2000, all this came to an end with the stock markets crashing, and dotcom companies rebranded as “dotbomb” companies.

But while many companies disappeared, the internet did not, and technologies associated with the internet evolved. The ecommerce pioneered by Amazon got better and better. Of dozens of search engines, Google emerged as the most useful one. This reminds me of Web3 today. Try to buy land on Decentraland for example, and it is a cumbersome experience. Currently Web3 is slow, reminiscent of AOL dial-up. And for what use?

Therefore, while I believe the metaverse or Web3+ is not a thing yet, it will be a thing that will change the way we live our lives, the way we work, and play. This translates into enormous opportunities for companies and brands — but only those that solve real problems and major challenges. This is something I explained in my last book (The Interaction Field, PublicAffairs 2020).

Look at the companies that have thrived over the years — Amazon solved a real problem and made shopping for anything much more efficient via ecommerce. Google helped you find things on the internet via the technology of search engines. Uber and Lyft helped us get around town in a relatively cheap, convenient way that beats waiting for a taxi, especially in NYC when it rains.

The problem with the metaverse and Web3+ seems to be that we’ve forgotten this simple principle of solving something for consumers and society. Buying a Bored Ape or selling an NFT collectible or dressing up your avatar with your favorite fashion label is something we’re doing not because we should but because we can. Currently we’re trying too hard to be amazing, rather than being amazingly useful, as Jaer Baer, a branding strategist, has said before.

In the next article, I’ll introduce a framework and model to really see the big opportunities that these emerging technologies associated with the metaverse or Web3+ present for companies and brands.

To be continued in Part 2.

DOWNLOAD THE FULL ARTICLE SERIES BELOW

[1] “Why is Snoop Dogg talking about Web 6.0”

[2] Other tech luminaries have followed Zuckerberg’s lead. By December, Jack Dorsey co-founder of Twitter and Square announced rebranding it to Block in an effort to position the payments company on new technologies that underlie the metaverse, such as blockchain.

[3] “Microsoft Chief Hails $75 billion Deal for Activision as Grand Step Into the Metaverse,” Financial Times, February 2, 2022

[4] “Facebook’s CEO on Why the Social Network is Becoming ‘a Metaverse Company” Casey Newton, The Verge, Jul 22, 2021

[5] Meta Founder’s Letter, October 28, 2021, Mark Zuckerberg, https://about.fb.com/news/2021/10/founders-letter/October 28, 2021

[6] “Opportunities in the metaverse: How businesses can explore the metaverse and navigate the hype vs. reality” JP Morgan Onyx by JP Morgan February 15, 2022

[7] “Why Wall Street thinks the metaverse will be worth trillions,” Bernard Warner, Fortune, January 27, 2022

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Meet Me in the Metaverse,” Technology Vision 2020, Accenture

[10] Elon Musk Interview, Babylon Bee, December 22, 2021

[11] “CES 2022 brought pieces of the metaverse into view,” Ina Fried, Axios, January 7, 2022

[12] “Bored Apes, BuzzFeed and the Battle for the Future of the Internet,” Maxwell Strachan, Vice, February 14, 2022

[13] “Meet Me In the Universe,” Technology Vision 2022 Accenture 2022

[14] “CES 2022 brought pieces of the metaverse into view,” Ina Fried, Axios, January 7, 2022

[15] Wikipedia description of Snow Crash

[16] “The Sci-Fi Guru Who Predicted Google Earth Explains Silicon Valley’s Latest Obsession”; Joanna Robinson, Vanity Fair, June 23, 2017

[17] “Why the Metaverse Will Change the Way You Work,” Sarah E. Needleman, The Wall Street Journal, Feb. 7, 2022

[18] “Metaverse virtual worlds lack adequate safety precautions, critics say,” Maura Barrett and Douglas Forte, NBCNews.com, Feb. 9, 2022

[19] Alex Dovbnya (2022), “Crypto Winter? “Black Swan” Author Predics Full-Blown Ice Age,” UToday, June 2022

[20] See McKinsey; CBInsights 2022: Metaverse of Madness and Fahri Karakas (The Goldrush has started in the metaverse….)

[21] Thank you to Alberto Velasco and Luis Geradin for valuable comments on earlier drafts of this article